06 Aug INTERVIEW YAN BREULEUX – What was the atmosphere like at ISEA1995? ?

In 1995, we found ourselves in the midst of a technological utopia. It was the post-Netscape technology bubble, and the first multimedia web browser had just hit the consumer market. Fresh out of university with a diploma in visual arts, I was hired as an intern at Zones Productions (a collaborator of ISEA at the time). On my first day, I was asked to hook up the building’s Internet connections. Being primarily trained in video art, I had very little knowledge in IT. After a few days of wrestling with my first 14,4 kbps modem, I finally managed to gain access to the Internet using Mosaic. As an artist, a huge wave of excitement washed over me when I contemplated the expressive and broadcasting possibilities of the web. By the time I learned how to properly handle multimedia devices, hypermedia was already well on its way to prominence.

I used to eagerly wait for the new issues of Wired magazine. With spectacular images and catchy slogans, the magazine’s editor at the time, Nicolas Negroponte, had the amazing capability to conjure digital utopias in their reader’s minds. Wired often touched upon the expressive and narrative potential of the web, and the new forms of interactivity it offered. Therein floated this idea of a second renaissance. The general ambiance at the time was thick with technological effervescence and the need to explore new artistic and theoretical territory. In addition, a “revolutionary” optical storage format was unveiled to the world; the CD-ROM. Newly developed imaging software quickly made use of this fascinating leap in tech. In the early days, each software update promised more in terms of real-time interaction with video, sound and animated visuals. Being curious by nature, I explored these programs by creating animated visuals for raves.

Early in my career, I often ran into Michael Century while walking the halls of Zones Productions. I didn’t know who he was, but by the way people behaved agitatedly around him, I assumed he occupied an important position in the organization. In fact, he was directly responsible for the Tunnel sous l’Atlantique project, by Maurice Benayoun. I also encountered Char Davies, and the founder of SoftImage, Daniels Langlois, who later became a prominent figure in the conservation of digital arts. Initially unaware of who these people were, I learned about them while attending the first ISEA symposium. I met with the symposium’s director and founder of SAT (1996), Monique Savoie, as well as Mutek’s now artistic director Alain Mongeau.Experiencing ISEA’s first symposium greatly contributed to my initiation into the vast universe of research and experimentation, which has stuck with me ever since.

In my opinion, ISEA1995 was to Montreal an event of equal importance to Expo 67. The symposium was held at a thriving technological period, and marked the advent of the democratization of digital technology in our city. ISEA represents to me my very first contact with the artistic spirit found in new technologies.

Is there an artwork, exhibition, or panel you vividly remember?

There are two works of art that I remember particularly well: Model5 by Granular Synthesis and Le Tunnel sous l’Atlantique by Maurice Benayoun.

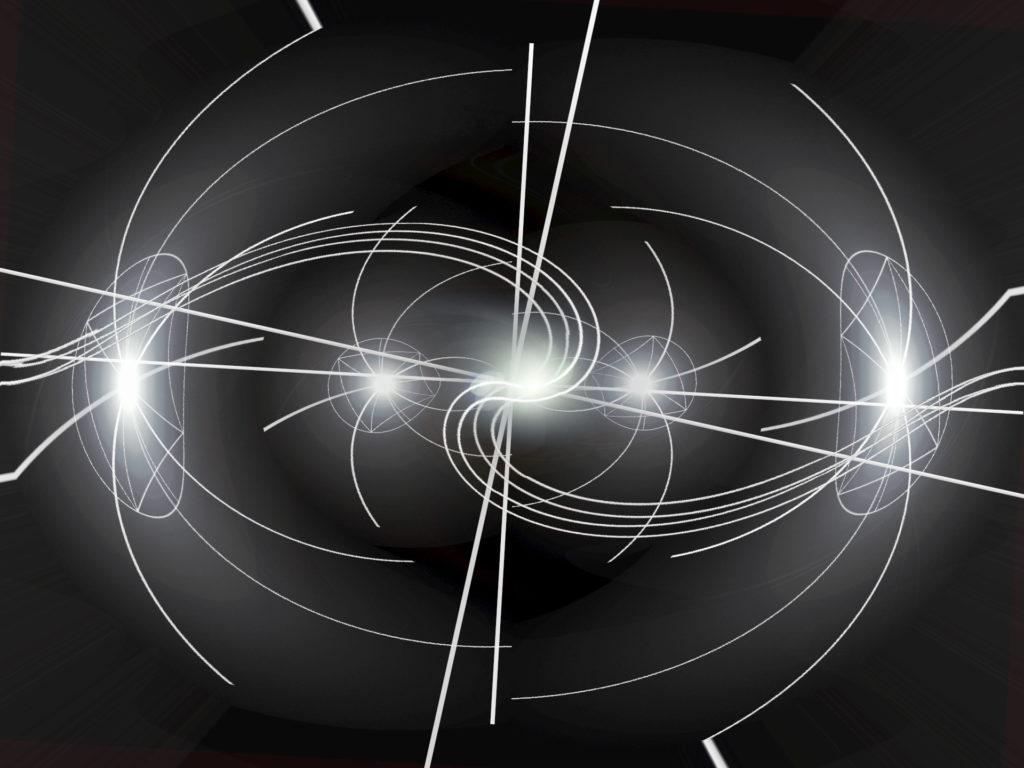

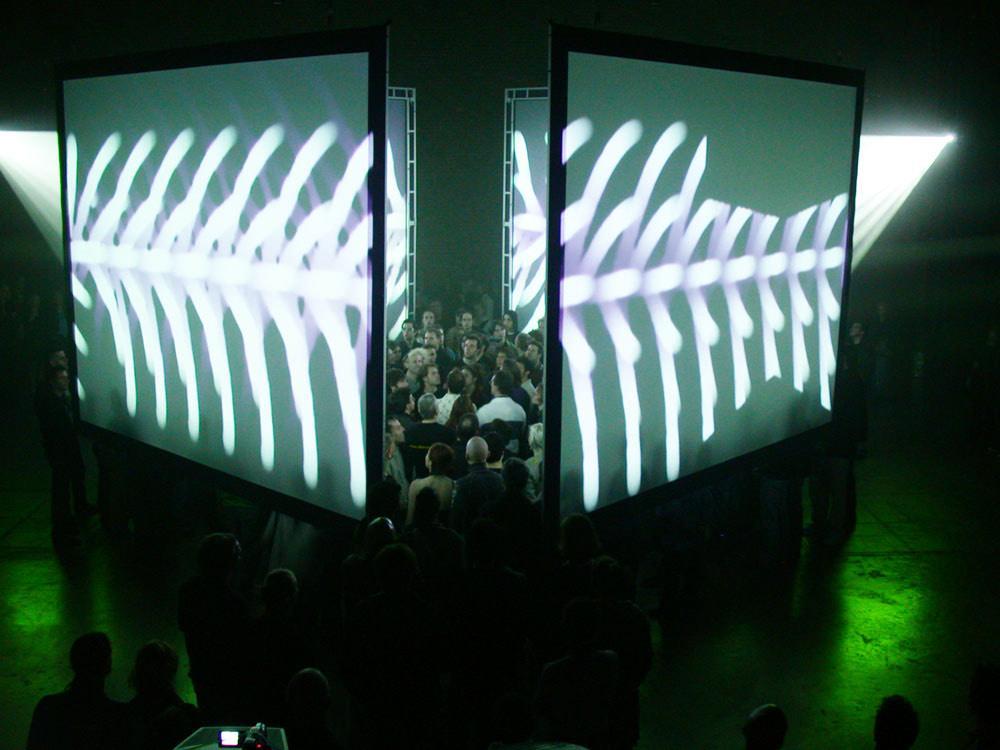

Model5 rattled me deeply for its brutal visuals, unyielding musical score. Its image repetitions and overall structure entirely changed my perception of art. The rumble of sound waves echoing through my ribcage, accompanied by the hypnotic repetition of images initiated me into a practice that would only find its name in 2010: A/V performances. After experiencing it, I felt as though I had been launched into the future. In their work, Granular Synthesis expressed something so similar to my artistic intentions and with such force that, upon leaving the show room, my mind was overwhelmed with ideas. A new world of possibilities opened up to me, and I desperately needed to study its vocabulary. Everything I’ve created since can be traced back to that experience, from my approach to sensory stimulation to immersive narrative experiences. Partnered with Alain Thibault under the name of Purform, I channelled this inspiration into the subsequent creation of Noise, Clima(x) and ABC-Light (which received an honorable mention at Ars Electronica in 1999). To this day, I remind my students that encountering an oeuvre that expresses what they are struggling to express themselves, is a good sign. Granular Synthesis went on to become a hallmark of the ELEKTRA Festival, where they often present their newest experimentations. I attend the event every year, impatient to witness the evolution of their artistic practice. In 2007, I experienced another artistic upheaval upon witnessing Kurt Hentschlager’s Feed (a former member of Granular Synthesis).

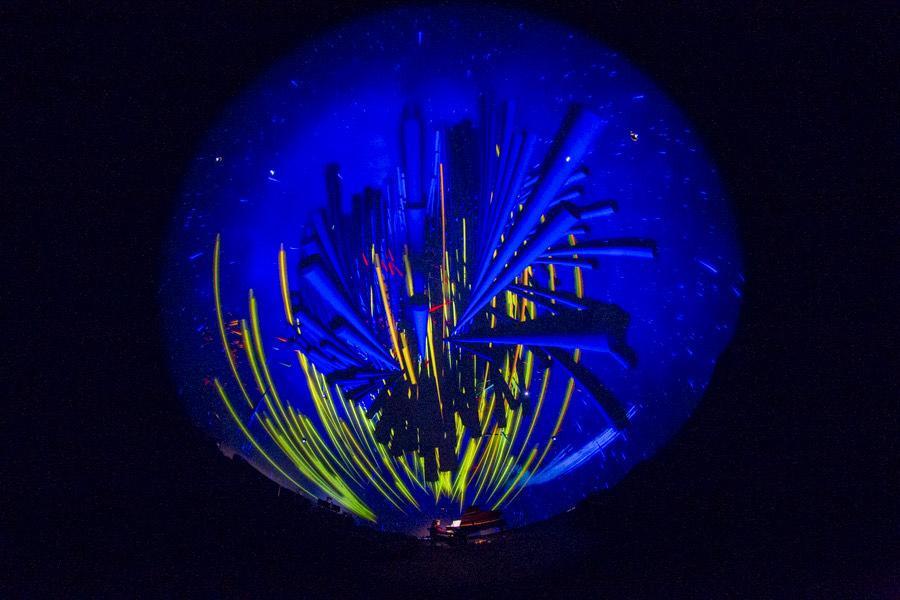

At ISEA1995, I was also deeply impacted by Maurice Benayoun’s Tunnel sous l’Atlantique. I knew of Benayoun through his work as a 3D artist on the TV show “QuarXs vs QuarKs”, which had an impressive rendering quality for its time. Tunnel sous l’Atlantique was such a revolutionary project that I initially dismissed it as totally infeasible: Powered by a 100 000$ Silicon Graphics computer, Benayoun constructed a generative sound system controlled by the movements of participants as they navigated a virtual environment. The performance also featured a couple, divided by the Atlantic Ocean, meeting in said virtual environment.

To truly grasp Tunnel sous l’Atlantique’s impact, it’s imperative to understand the technological leap it represented: before Skype, communicating through video vignettes while floating around in a virtual 3D environment generated in real-time was a jaw-dropping feat. Being a freshly trained art major impassioned by the world of computers and 3D animation, this experience opened up a new radical reality to me, and has continued to inspire my practice to this day.

Today, with the rapid acceleration of telecommunication technologies, I can only reminisce on those early attempts at real-time video transmissions over T4 cables (four phone lines fused together). The year 1995 certainly marked a turning point in multimedia technology and hypermedia. New technologies left the secluded confines of specialized research laboratories to mingle with the rest of academic, artistic and professional practices (such as dance, music, theater, performances, etc.) the meeting of the fields of art and technology gave rise to a new wave artistic vocabulary.

Did attending ISEA 1995 alter your path in an important way either professionally, artistically, or otherwise?

I would say that I met my artistic family at ISEA!

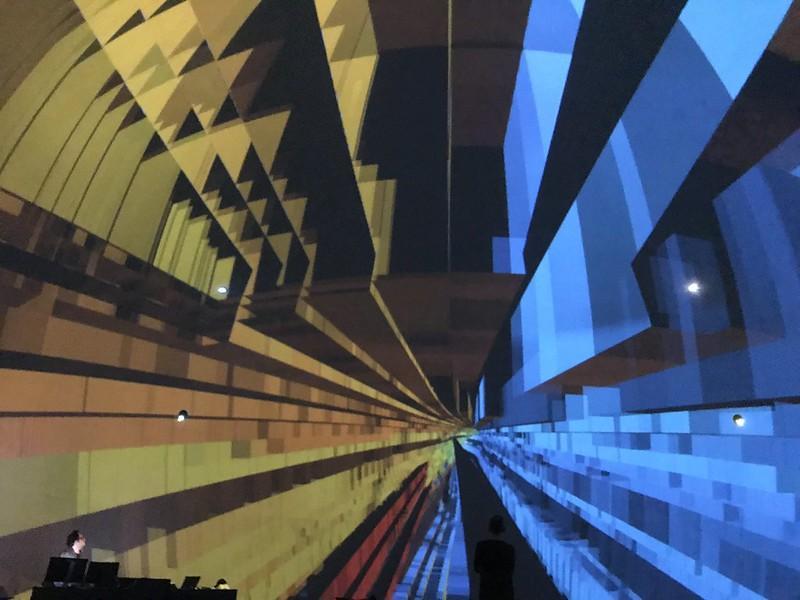

ISEA opened the door to a lot of friendly relationships I would’ve otherwise missed: in 1995, I must have worked 60 hours a week. I practically lived at Zones Productions. I was busy exploring new creative contexts and seizing every opportunity to collaborate, and I met some very fine artists along the way: I developed assets for Michael Mackenzie’s Dark Practice Scarring, I participated in the design of an interactive multimedia application for Maurice Benayoun’s Tunnel sous l’Atlantique, and modelled 3D environments for Jean-François Cantin. I also collaborated with artistic collectives such as LCD25 and Synergy, who would often do work for rave venues. I was already aware of Synergy’s work before collaborating with them. Their architectural video mapping techniques were definitely ahead of their time.

ISEA1995 also introduced me to the logic behind academic research in technological arts. Indeed, I met Luc Courchesne, professor of industrial design at the Université de Montréal, for the first time at ISEA. He would later become my Masters’ director. My doctoral thesis examined the nature of the relationship between audio and visual elements in A/V performances, an interest that also burgeoned during my first ISEA symposium. Ultimately, meeting all the fascinating artists in attendance at ISEA1995 had such an impact on my practice that it altered the course of my academic career.

I first attended ISEA as an artist, later as a researcher. Currently, my interests naturally align with ISEA’s artistic and academic community, since I am intrigued by issues regarding virtual archives.

Since ISEA returns to Montreal this year, understanding its historical link to the city is certainly important. Could you summarize ISEA1995’s legacy?

The symposium endowed Montreal with a certain level of legitimacy as a hub of artistic expression, techno culture and practice-based research. Montreal’s role as a global capital for digital creativity and cultural industries is largely due to ISEA1995’s initial spark.

A year after directing ISEA1995, Monique Savoie founded the SAT in the same building where the symposium had been organised. Over the years, they have hosted several memorable multimedia events, often organized under the designation of Epsilon Lab. Four years later, Alain Mongeau founded Mutek. His influence spreads across numerous countries, becoming a leading figure of the global electronics scene. Additionally, Granular Synthesis (whose artistic director presented a concert at ISEA) has established itself as a staple of ELEKTRA. Other renowned A/V performance artists have joined their ranks, such as Rioji Ikeda, Ryoichi Kurokawa, Herman Kolgen, Incite, Matthew Biederman, Kurt Hentschlager, Ulf Langheinrich, Carsten Nicolai, Otolab, Jean Piché, Edwin van der Heide, Tvestroy, Semiconductor, Anti vj, Amon Tobin, Richie Hawtin, etc.

While Expo67 remains memorable for the “Pavillon du Canada” and the first demonstration of an IMAX system, ISEA1995’s impact may be just as important. In spite of being of a different academic and artistic nature, ISEA1995 inspired several local artists and thinkers to launch initiatives that cemented Montreal’s status as an international electronic arts scene. Teachers, researchers and theorists from all over the world have taken advantage of the ensuing editions of the symposium to share their findings, thus ensuring the pervasiveness of technological arts across the world.

Since ISEA first came to Montreal in 1995, what would you identify as the most important technological development for your practice and/or in relation to the aims of ISEA. That is, what’s the advance in technology you find to be most pressing or impactful, or maybe what surprised you the most from then until now?

My answer to this question might have been different three months ago.

The global technological climate is rapidly evolving, and I feel the beginnings of a new utopia brewing at the edges of communication technologies and artificial intelligence. However, although I have been participating in telecommunication events since the late nineties, I still tend to believe that telecommunication technologies ought to be approached as alternative realities. Indeed, they possess an artistic and academic language of their own. They do not replace, but rather optimise and accelerate certain forms of communication.

A large number of technologies that we use today were already present (though perhaps at a smaller scale) during the nineties (immersive devices, telecommunication, digital displays, multi-projections, spatial sound systems). Indeed, Evans and Sutherland’s 1965 article Ultimate Display describes in detail the underlying logic behind virtual and augmented reality. Luc Courchesne had been experimenting with novel digital displays and interactive video well before 1995. A year prior to ISEA1995, Henry See (member of ISEA’s administrative council) constructed a video installation that reacted in real-time to the audience’s movement. At this same exhibition, the duo Louis-Philippe Demers and Bill Vorn likened their installation, Espace Vectoriel, to a reactive environment possessed by a form of artificial intelligence. Then, only a few months before ISEA1995, Char Davies unveiled an immersive virtual reality oeuvre at Montreal’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Titled Osmose, the head-mounted virtual-reality displays represented a significant advance in the use of emerging media in art.

In that sense, one can easily look back onto the past and realise that innovation is relative, especially in what comes to technological progress. The underlying interdependences between a system’s various components rules out the idea that technological development progresses in a linear fashion (except maybe micro-processors according to Moore’s law). In fact, the phenomena of “planned obsolescence” regularly interferes with said progress. Additionally, it is possible to gain more control over image resolution, to the detriment of real-time control. That being said, tremendous strides have been made in terms of computer performance, control and miniaturization. This progression specifically has most certainly furthered accessibility (or democratisation) to digital technologies. It’s also worth underscoring the growing importance of human-computer peripherals, further bridging the gap between man and machine.

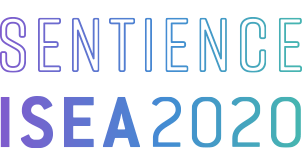

Looking back, I can’t think of one particular piece of technology that most influenced my practice. Although a few years after ISEA1995 I was especially taken by the advent of video mapping (which I learned about during a residency at the SAT). In 2003, Sébastien Roy developed an automated video calibration system that adapted projections to irregular surfaces. Coincidentally, I had been struggling with curved projection surfaces while working on Ars Natura a year prior. In creating this immersive 180 panoramic oeuvre, I came to better understand how to direct the attention of spectators using spatialized sound and visuals. Video mapping technology eventually led to the creation of the Stratosphere Dome at the SAT, a device with which I have worked extensively over the last 10 years.

In my opinion, the exploration of new artistic languages and their transversal issues, like those found in sound visualisation, experiential design, mise-en-scene, new narrative forms, is at the core of the ISEA symposium.

Related to the previous question, since 1995, is there a particular theoretical development you’ve felt most significantly or you believe to be especially consequential?

In regards to the evolution of practices in the technological arts, things have changed tremendously since 1995. Informal discussions had during reunions at Hexagram (the research-creation network), notably with Chris Salter and Jean Dubois, point towards a shift away from a paradigm anchored in technology, towards a paradigm more closely associated with practical knowledge and practice-based research. In this context, innovation emerges naturally from the association of different research sectors. Indeed, there has been a definite increase in interdisciplinary exchanges between experts and practitioners, especially in the field of public art. These exchanges often lead to organized events axed on the democratisation of technology, blurring the lines between amateurs, professionals and researchers. In that sense, Louis-Claude Paquin and Cynthia Noury’s recent survey and mapping of research-creation gives us a clarifying glimpse into the vast array of novel methodological approaches specific to this form of research. In fact, according to Hexagam’s current leanings, interdisciplinary collaboration between professional artists and academic theorists is highly encouraged.

I believe interdisciplinary collaboration fosters an environment that promotes escaping or subverting technological determinism (which often dictates and orients creative practices). In my opinion, our current model of technological development ought to lean more on social qualities than economic ones.

Furthermore, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking on the subject of archives in the context of media archaeology, based on the work of Jussi PariKka, Erkki Huhtamo and Oliver Grau. I find their archaeological approach interesting, since it allows researchers to explore what is “new” in old technologies, and vice versa. As such, it shifts the dialogue away from a paradigm axed on technical progress towards something more ethical, giving researchers the opportunity to examine the social impact of technological obsolescence.

Shifting from what’s changed to what’s stayed the same, is there anything you remember from ISEA’s first time in Montreal that seems as clear, or as resonant today as it did then, and why?

Today, ideas of collective intelligence, introduced at ISEA1995 by Roy Ascott (also known for his concept of telematic arts), have taken on new significance. Since the very beginning, Ascott understood how the paradigm of cybernetics has influenced the exchange and co-construction of messages mediated by communication technologies in artistic productions. Currently, Ascott’s research takes on a whole other aura in light of telecommunications’ current role in society.

Maurice Benayoun’s Tunnel sous l’Atlantique, with its shared virtual environment and telepresence vignettes, is an artwork of rare quality that is just as relevant today as it was 25 years ago. Tracking the movements of spectators using their rib cages as capture points was a radical innovation, which has yet to be fully explored. That being said, Kurt Hentschlager used a similar process during his performance Feed at the ELEKTRA Festival in 2007.

The initial dream of a new form of information dissemination and the promise of collective intelligence, have met some resistance, especially with the recent evolution of the GAFAM. Although people still use “wikis” and participate in numerous online communities, the truly open and free system dreamed of since the early days of the internet will continue to be questioned for years to come. The ideal of democratisation and dissemination of artificial intelligence appears to be following the same trajectory once experienced by earlier web multimedia: the tools of artificial intelligence are becoming more and more accessible. In light of the theories of second-order cybernetics and recent developments in artificial intelligence, I predict important changes in the way we will conceive future new technologies.

Finally, thinking about this year’s theme, there might be something a bit ironic about exploring the notion of sentience (historically reserved for biological life, and quite a small subsection of it) through digital media and electronic arts. There’s been much work done in the past 25 years to loosen the boundaries between such distinctions: how do you imagine ISEA2020 helping in that?

The similarities shared between humans, animals, and machines are fundamental in cybernetic sciences. According to the founder of cybernetics Norbert Wiener, the main tenets of the information paradigm – the notion of feedback – can be applied to humans, animals as well as the material world. Famously, the AA predictor (as analysed by Peter Galison in 1994) can be read as a first attempt at human-machine fusion (otherwise known as a cyborg).

The infamous Turing test also tends to blur the lines between humans and machines, between language and informational systems. Second-order cybernetics are often associated with biologists Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana. The very notion of autopoiesis (a system capable of maintaining a certain level of stability in an unstable environment) relates back to the concept of homeostasis formulated by Willam Ross in 1952. Moreover, the concept of “ecosystems” emanates directly from the field of second-order cybernetics, providing researchers with a clearer picture of the interdependencies between living and non-living organisms. In light of these theories, the absence of boundaries between animals, humans, and machines constitutes the foundation of the technosciences paradigm. New media, technological arts, virtual arts, etc., partake in the dialogue between humans and machines, and thus contribute to the prolongation of this paradigm. Frank Popper nearly called his book “Techno Art” instead of “Virtual Art”, in reference to technosciences (his editor suggested the name change). For artists in the technological arts community, Jakob von Uexkull’s notion of “human-animal milieu” is an essential reference. Also present in Simondon’s reflections on human environments (both natural and artificial), the notion of “milieu” is quite important in the discourses about art and the environment. Concordia University’s artistic community chose the concept of “milieu” as the rallying point of its research laboratories.

ISEA2020’s theme resonates particularly well with the recent eruption of processing and artificial intelligence technologies. For me, Sentience is a purely human and animal idea: machines can only simulate our ways of thinking and feeling. Partly in an effort to explore the illusion of sentience in computers, Louis-Philippe Rondeau, Benoît Melançon and I have established the Mimesis laboratory at NAD University. Processing and AI technologies are especially useful in the creation of “digital doubles”, “Vactors”, real-time avatar generation, Deep Fakes and new forms of personalised interactions.

I adhere to the epistemological position that the living world is immeasurable. Through their ability to simulate, machines can merely reduce complex logics to a point of understandability. The utopian notion of empathetic computers is an idea mostly explored by popular science-fiction movies. Nonetheless, research into computer sentience allows us to devise possible applications, explore notions of embodiment and agency, and thereby develop new forms of interaction. Beyond my own point of view, the idea that machines can somehow feel emotions gives artists and researchers the opportunity to experiment with certain findings from the fields of the cognitive sciences, computer sciences and interactive design. For example, in 2002 I was particularly marked by an immersive installation at Universal Exhibition in Neuchatel, Switzerland titled Ada: Intelligence Space. The installation comprised an artificial environment controlled by a computer, which interacted with the audience on the basis of artificial emotion. The system encouraged visitors to participate by intelligently analysing their movements and sounds. Another example, Louis-Philippe Demers’ Blind Robot (2012), demonstrates how artists can be both critical of, and amazed by, these new forms of knowledge. Additionally, the 2016 BIAN (Biennale internationale d’art numérique), organized by ELEKTRA (Alain Thibault) explored the various ways these concepts were appropriated in installation and interactive art. The way I see it, current works of digital art operate as boundary objects. The varied usages and interpretations of a particular work of art allow it to be analyzed from nearly every angle or field of study. Thus, philosophers can ask themselves: how does a computer come to understand what being human really is?

I have yet to attend conferences or exchange with researchers on that subject. Although the sheer number of presentation propositions sent to ISEA2020, I have no doubt that the symposium will be the ideal context to reflect on the concept of Sentience and many issues raised therein.